At this point, stablecoins are a demonstrated success — crypto’s first killer app. The data on this front is abundant and increasingly clear. As I have argued, stables have dollarized the crypto market, and they are crypto-dollarizing a whole host of economies, particularly in emerging markets. There is an important discussion to be had about the long term prospects for native tokens like Bitcoin, Solana, or Ether in a world where almost all transactions on chain are settled in stables, but that is a question for the crypto-natives to grapple with.

What I am interested in here is what the post-stablecoin world looks like. It’s apparent to me that stables are becoming a truly dominant global settlement infrastructure, and one that is increasingly integrated into the existing financial system. As I have laid out, I believe stables are the new Eurodollars, and once they reach critical mass (perhaps in the $300-$500b range (versus their $160b float today), the Federal Reserve and other major central banks will be forced to integrate them into their financial toolkit, rather than impolitely ignoring them as they do today. This would mirror the transition that Eurodollars went through in the early ‘70s.

Thus, I would like to graduate the discussion from its current state that mostly centers on the prudence of creating stables, whether they can hold their pegs in the long term (see eg this paper from the BIS), whether they can be accepted as a true money substitute (see eg Gorton and Zhang), and consider a world in which stables continue to thrive and ultimately achieve ubiquity. Already, some former and current policymakers have begun to adopt this posture, considering not the question of “should stablecoins exist?” but rather “assuming stablecoins, then what?” It’s these thinkers — specifically Fed Governor Chris Waller, former CFTC chair Timothy Massad, and former Comptroller Brian Brooks — that I want to focus on. However, in an effort to capture the entire spectrum of debate, I’ll start with more skeptical views espoused by Rohan Grey and academics Gorton and Zhang.

1. Greyism: Stablecoins are bad because they are unregulated bank deposits

I initially wanted to start with Sen. Warren to represent the most dogmatically anti-stablecoin perspective, but since Warren is generally opposed to most things crypto, I don’t think she is the most representative voice. Her anti-stablecoin stance isn’t particularly notable within the broader cluster of her crypto contrarian views, so she isn’t necessarily the best example of a critic.

Instead, I am selecting Rohan Grey to represent what I think is an internally consistent anti-stablecoin perspective. I find Grey’s views on stablecoins interesting because they appear to be principled, but from virtually the opposite side as me. Grey is a legal scholar who notably helped author the STABLE Act introduced by Rep. Tlaib in 2020. The STABLE Act (which didn’t pass) was arguably a reaction to Facebook’s doomed Libra ambitions. It mandated that stablecoin issuers obtain bank charters, asked for them submit to oversight from the Fed and FDIC, and generally behave like banks. Suffice to say, regulating stablecoin issuers in this manner would have effectively destroyed the stablecoin industry.

From what I recall, when crypto people pointed out that this would go beyond stablecoins and effectively condemn fintechs like Paypal to bank regulation (since stablecoins and Paypal dollars are substantively the same), Grey and those in his camp bit the bullet and said “ok”. My understanding of his position is that fintechs and stablecoins and other near-money, nonbank depository instruments should in fact be folded into the more highly regulated bank system. Grey on several occasions described stablecoin issuance as “counterfeiting”.

Interestingly, Grey is supportive of financial privacy for individuals, but feels that private sector issuers are unlikely to provide it; or even if they are providing sufficient privacy, the fact that this is happening outside the guardrails of the regulated banking system makes it unacceptably costly (since stablecoin issuers will ultimately, in his view, require a bailout). If unregistered deposit-taking ends up with a bailout and taxpayers are guaranteed to be on the hook in the end, why not just regulate them as banks in the first place?

I will say, I understand the moral logic here. If unregulated deposit-taking and dollar liability issuance ends with issuers moving up the risk curve and developing asset-liability mismatches (like Terra’s UST), and stablecoins reach systemic size, you could end up with shadow bank crises that require government intervention. The “deal” that banks make with the government as public-private partnerships is that they are backed by the FDIC and other government liquidity facilities and have to submit to regulation and supervision, and in exchange, are allowed to engage in lending with the savings of ordinary citizens. Because household savings cannot politically be allowed to evaporate, the government has to be involved both in terms of supervising banks and in terms of providing a liquidity backstop. Stablecoins and other unregulated issuers, the argument goes, are wagering the savings of individuals and firms that deposit with them, without submitting to the other side of the deal (supervision and depository insurance). So they are essentially getting something for nothing.

My reactions to this are fourfold. First, stablecoin issuers seem to be getting more risk averse with time. Tether used to hold all kinds of unusual assets on their balance sheet, but now they mostly hold short duration treasuries. Circle had a snafu with SVB and drastically reduced their exposure to cash in banks. Newer stablecoins seem to be prioritizing bankruptcy-remoteness and structures that privilege holders in liquidation. Paypal’s PYUSD is a standout, operating under a NY Trust License with a bankruptcy remote model. In fact, PYUSD is so ironclad that it’s even more secure than conventional user funds held with Paypal. Stablecoins like PYUSD are regulated by a sophisticated state regulator; it’s a stretch to consider them opaque shadow banks.

Additionally, there now exist a number of ratings firms — both crypto-native ones like Bluechip, as well as S&P and Moodys — that help the general public understand the risk of stablecoins. Overall, my assessment is that the stablecoin space has reacted really well to the failure of UST and has become much healthier overall in the last two years. It’s unclear to me how much additional regulation is needed. The stablecoin regulations we are seeing globally seem to be acknowledging this, rather than forcing stables into the ill-fitting rubric of bank regulation.

Third, it seems like deposit-taking and lending are being decoupled anyway. Firms and households are increasingly holding treasuries directly, enticed by higher yields that aren’t passed along in savings accounts. Banks are increasingly not lending out customer deposits, but rather parking cash at the Fed (and sometimes outsourcing the capital side of lending to private lenders, as Matt Levine points out). So “narrow banking” is becoming increasingly popular. Stablecoins and money market funds are effectively a form of narrow banking. This does potentially reduce the importance of commercial banks as a financial intermediary, but this isn’t just a stablecoin thing. It’s a systemic change that financial regulators will have to grapple with eventually.

Lastly, on privacy, I feel that stablecoins do offer a fairly good blend of both privacy for individuals and transparency for illicit actors. Because blockchain analysis is fairly hard, in practice most on-chain deanonymization efforts tend to focus on significant financial crimes. Grey’s preferred solution is a government-run digital cash product that offers similar privacy to physical cash (at least in small denominations). But to me it doesn’t seem like the government is at all interested in financial privacy (quite the contrary, if you followed the Samourai or the Tornado cash cases), so I find it highly unlikely the state would be a reliable sponsor of a private digital cash system. Stablecoins in my view are a reasonable middle ground. The big baddies are frequently identified and have their funds seized, while ordinary citizens going about their business can have reasonable (if not perfect) privacy assurances.

2. Gorton and Zhangism: Stables don’t work in theory, so they won’t work in practice

Following Grey’s rather principled rejection of stablecoins, we move on to two economists who simply refuse to incorporate the existence of stablecoins into their model of the world. I speak of Gary Gorton and Jeffery Zhang who wrote an infamous paper in 2021 entitled Taming Wildcat Stablecoins.

Gorton is a professor of economics at Yale and Zhang was formerly an attorney at the Federal Reserve, now a law professor at Michigan. This is an important paper because it typifies an entrenched establishment belief: stablecoins represent a return to the US “free banking” era that was riven by crises and bank failures. Ergo, stables themselves are likely to be an inferior form of money. Paul Krugman recommended the paper, and the same talking points were echoed by St Louis Fed president James Bullard and Senator Elizabeth Warren. Central bankers simply love to invoke the antebellum “free banking” era to attack the stablecoin sector.

The only problems: the US free banking episode in the 1830’s-60s wasn’t “true” free banking (and hence not that useful as an analogy), and stablecoins aren’t really all that similar to free banks.

As I wrote in my Coindesk piece at the time, the US version of “free banking” wasn’t exactly a representative episode. Free banking refers to a setting in which banks operate without central bank oversight and charter issuance is relatively open. Scotland is the archetype, and that system was stable for over 100 years. As I wrote:

The American antebellum episode did not constitute genuine laissez-faire banking. Banks during that period were forced to hold risky state government bonds and were restricted from engaging in “branching” — meaning they couldn’t establish branches nationwide. This inhibited them from geographically diversifying their depositor base and from having free choice in their asset portfolio. It’s no wonder that bank failures were common.

In the US free banking period, bank failures were common, but that’s because banks themselves were fragilized due to regulation which prohibited them from diversifying their deposits, and forced them to hold inferior assets. Other forms of genuine free banking such as that found in Scotland in the period were genuinely unrestricted, and much more successful and stable, as George Selgin has spent a career pointing out. The fact is, proper free or “laissez faire” banking has a long track record of creating stable, crisis-free financial systems. The US episode that American policymakers fixate on simply isn’t a good example of the phenomenon.

Additionally, it’s misleading to compare stablecoins to banks as they aren’t engaged in maturity transformation or risky lending. Mostly, they hold short term US Treasuries or overnight repos, which are highly liquid, short duration assets. And stablecoins, though they do occasionally suffer redemptions, distribute liabilities to global, heterogeneous userbases and thus are less exposed to acute liquidity crises such as those faced by tiny regional banks (which was the problem with the US “free banking” system).

Because they find stables analogous to banknotes issued by banks that sometimes traded below par, Gorton and Zhang assert in their paper that stablecoins do not satisfy the “NQA” (no questions asked) principle. NQA “requires that the money be accepted in a transaction without due diligence on its value.” For them, MoE is downstream of NQA. As they say, “it cannot just be assumed that an object will be used as a medium of exchange. For that to happen, the object must satisfy the NQA principle.” So they conclude that stables are a poor MoE because they believe that users cannot ever have complete faith that a given stablecoin can be exchanged or redeemed at par.

This is an interesting case of reasoning from the armchair. While stablecoins have historically faced crises, if you ask a stablecoin user today whether they review the Tether or Circle balance sheet before each transaction, they would laugh at you. It is empirically observable today that stablecoins are used as a dollar substitute not just for crypto purposes, but for general digital dollar activity by tens or hundreds of millions globally. The vast majority of the time, major stablecoins trade at par on highly liquid markets, both on DeFi and centralized exchanges globally. Deviations from the peg are quickly arbitraged away.

Additionally, the dogmatism of G&Z regarding NQA is questionable. Few doubt the quality of commercial bank money, and it’s generally treated as functionally identical to central bank money (cash). However, during the bank crisis of 2023, the quality of deposits in certain banks above the FDIC limit of $250k was indeed called into question. For Silvergate, Signature, SVB, and others, there certainly were Questions Asked. Does this mean that commercial bank money is forever doomed to be considered unreliable? No, it simply means that users need to incorporate the possibility of bank runs (and possible government reactions) into their risk model. Similarly, UDSC had a depeg as some of it reserve in SVB were called into question in March 2023, but that doesn’t doom it forever. The stablecoin reacted and updated their reserve policy to de-emphasize exposure to commercial bank dollars, becoming more robust to future shocks.

As we often see with crypto critics, G&Z believe that because a certain system doesn’t work in (their) theory, it can’t work in practice. Yet in practice, stablecoins are thriving and going from strength to strength, and getting more embedded into the real economy. It’s clear that they are increasingly treated as a form of money, and it’s time that central bankers acknowledge that — or change their definition of money.

3. Massadism: We should engage with stablecoins, because they threaten sanctions enforcement

Recently, Brookings published a piece by Timothy Massad entitled Stablecoins and national security: Learning the lessons of Eurodollars. I encourage you to read it in its entirety.

Massad’s piece is one of the most remarkable discussions of stablecoins to date, not just because of its substance, but because of its author. Massad, a Democrat, was Obama’s CFTC chair and is no crypto booster. However he betrays an understanding of the stablecoin sector that is deep and realistic. His posture is not to ignore or write off stables as an ersatz form of money invented by crypto bros, but rather to acknowledge their success and to consider how their emergence affects US interests. (Compare him with certain progressives who simply want stables to not exist anymore, or with central bankers who think stables will be trivially replaced with CBDCs.) Massad’s piece focuses on the actual reality of stablecoins today and frames them as the successor to Eurodollars. This is a comparison that has also been made by folks like Izabella Kamiska and myself, more belatedly.

Massad makes a series of important observations. He points out the similarities between the emergence of Eurodollars and stablecoins:

- They represent dollar liabilities issued by entities outside the banking system (largely, but not exclusively in the case of stablecoins)

- They both emerged due to concerns around the use of US banks via entities who wanted to reduce their onshore risk (for eurodollars, Cold War adversaries, and for stablecoins, crypto traders who had been systematically debanked)

- They were both initially ignored by policymakers, and in the case of Eurodollars, ultimately accepted once systemically important

- A big portion of their growth stemmed from the opportunity to offer and earn higher yields than were available onshore

- They both cement the international role of the dollar, giving US policymakers strategic leverage (although this is less determined with stablecoins today)

Massad pinpoints an important difference between the two systems. Eurodollars, he points out, still ultimately require transactions to clear through US banks, which establishes a nexus of control that can be utilized for strategic purposes.

What he is chiefly worried about with stablecoins is their use for illicit finance, and in particular their possible undermining of our established sanctions regime. Massad acknowledges that known illicit stablecoin flows are still relatively minor, but he is concerned with a future in which they are more widely used.

Massad differs from some of his democrat colleagues by spurning the “let crypto burn” viewpoint held by many post FTX. He says that “crypto is not going away” and thinks that stablecoins could “arguably have greater potential to become a widely accepted medium of exchange for international payments” than CBDCs. Accordingly, he urges Congress to seriously consider stablecoin regulation, understanding that the US has more leverage if a larger share of stablecoins are issued by accountable, onshore firms. He understands that US crypto regulation must be situated within a global framework of competitive regulators. As he says: “ignoring the market on the assumption that it is small and can be contained could be risky, especially with other jurisdictions moving to permit wider use of stablecoins.” If the US pushes too hard against crypto, some regulator elsewhere will benefit, and this is already happening with stablecoins.

This is a viewpoint derived not from any fondness for crypto, but a serious acknowledgement of its successes and likely trajectory. I expect that Massad’s views will prove increasingly popular with members of his party as they realize that crypto is not dying off post the debacles of ’22, and that stablecoins are indeed thriving. Today, virtually all stablecoin metrics (aside from supply) are at all time highs. The empirical reality of the continued success of stablecoins, combined with positive regulation elsewhere, means that inaction is not an option for the US.

Massad ends the piece by musing about a few ways that stablecoins could be made to comply with sanctions enforcement, although he doesn’t settle on any single policy or technology. Encouragingly though, Massad doesn’t take the fire and brimstone approach of fellow Democrat Warren. With regards to stablecoin freeze and seize, he suggests “striking a balance between having adequate tools to detect and prevent illicit activity on the one hand and preventing unreasonable searches and seizures and protecting privacy on the other.”

While Massad and I almost certainly disagree about the merits of current US sanctions regime and the Bank Secrecy Act, his paper is a great example of pragmatic engagement with the stablecoin space. I hope he can make the case to more of his colleagues on the Democratic side.

4. Wallerism: Crypto, via stablecoins, is good for the dollar

Flipping over to the Republican side of the aisle, but remaining within the establishment, we have Federal Reserve Governor Chris Waller.

Waller pricked my ears in February with his comments in a speech entitled The Dollar’s International Role. The purpose of the speech is to defray concerns that the dollar is losing its status. Like Massad, he has an interest in maintaining the soft power that comes with sanctions-making ability, but he also stresses other benefits of the dollar’s globalized nature, such as lower borrowing costs for the Government and individuals, and insulating the US economy from macro shocks.

Though his comments on crypto were brief, they caught my attention. In his speech he says:

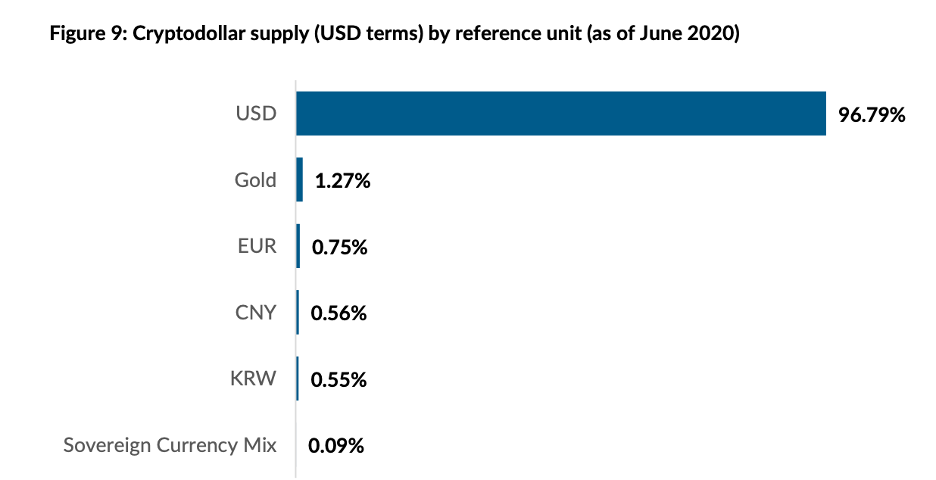

People often conjecture that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin may replace the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency. But most trading in decentralized finance involve trades using stablecoins, which link their value one-for-one to the U.S. dollar. About 99 percent of stablecoin market capitalization is linked to the U.S. dollar, meaning that crypto-assets are de facto traded in U.S. dollars. So it is likely that any expansion of trading in the DeFi world will simply strengthen the dominant role of the dollar.

And on this point, Waller is completely right. Around 60–80% of all value settled on blockchains is done with stablecoins, and over 99 percent of stablecoins reference the USD as their unit of account (and these are generally backed with dollar assets). New blockchains launch with native stablecoin integrations and this is a priority for every new L1 and L2 I’m aware of. Even Bitcoiners are focusing on stablecoins, after dismissing their importance for around a decade. From a data perspective, the overwhelming dollarization of the stablecoin sector has been consistent since we first pulled the data in 2020.

Today, the figure is higher, at over 99 percent dollars. To summarize the argument:

- Crypto activity (whether DeFi, perp trading, or spot trading) generally utilizes stables as the MoE and core collateral type

- 99 percent of stables reference the dollar, and this figure has actually been growing over time

- Ergo, crypto is good for the dollar.

As with Massad’s commentary, the argument itself isn’t necessarily that interesting, it’s who is saying it. Virtually anyone active in the crypto space should be aware of this line of reasoning, which is an inversion of the previously popular talking point that Bitcoin is displacing the dollar. But this is the first time I’ve seen someone at the Federal Reserve making this exact point. (As I was writing this article, I found some more prescient comments on stablecoins from Waller dating back to 2021 — this man knows his stuff).

Waller is a Republican and was nominated by Trump, but he’s no kook. He was confirmed in the Senate at the same time that gold standard-enthusiast Judy Shelton was rejected. He appears to have fairly conventional if dovish attitudes to monetary policy.

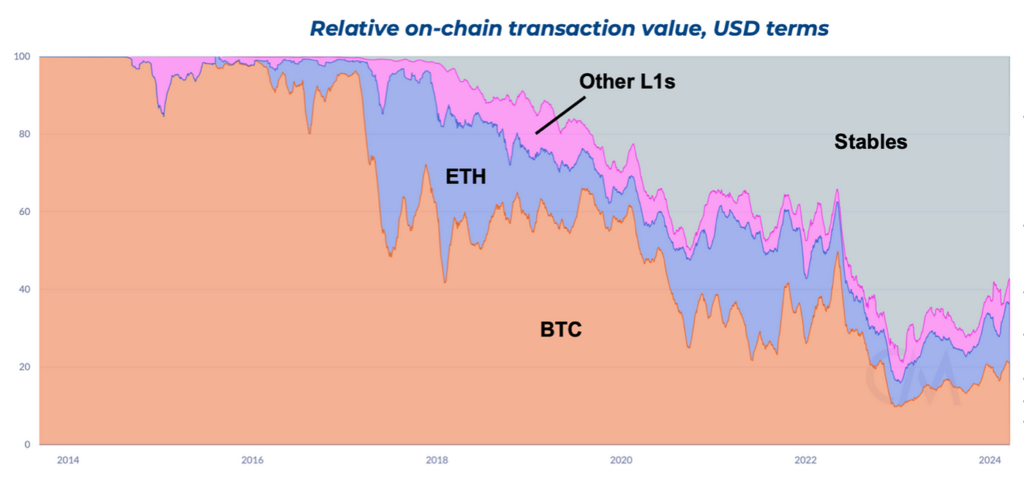

Regarding Waller’s argument, it’s worth imagining some scenarios in which it might break down. Starting with the first premise, that crypto is becoming dollarized, I don’t see how this trend would reverse. When I first pulled the data in 2020, stablecoin settlement value had grown to around 40% of all value settled on blockchains, and I thought the trend would continue.

I pulled this data again in 2023 for a series of talks and more recently in 2024 for a refresh. In 2023, stablecoins touched as much as 80 percent of value settled on chain. Keep in mind, this data is subjective and requires a considerable amount of denoising and spam elimination, so these figures aren’t exact. But the overall trend is clear — whereas Bitcoin and Ether were historically media of exchange within crypto, stablecoins are gradually displacing them.

This makes sense. Transacting in a volatile cryptoasset is simply more complicated from an accounting perspective. Everyone who traded prior to 2017 remembers Bitcoin as the unit of account for altcoin trades — but no one does this any more, as a volatile UoA is too mentally taxing to keep track of. If you’re purchasing goods with Bitcoin or Ether, you are subject to tax accounting, and you have to recognize a capital gain if the price appreciated during your holding period. And if you want to use a volatile cryptoasset as a bridge currency for remittances, for instance, you are subject to FX risk for the duration of the transfer. These are all frictions that naturally push people towards using stablecoins instead. As major stables like Tether and USDC have recovered from crises and regained their pegs after turbulence time and again, they have become highly trusted within the crypto space. Newer stables even offer real-time interest provision from the portfolio of underlying treasuries, eliminating the opportunity cost of using stables.

The main factor I can imagine that might undermine confidence in the stablecoin sector and push crypto users back towards BTC or ETH as media of exchange would be if stablecoin settlement assurances were significantly impaired. This could happen if, in response to government edit, the seizure rate of stablecoins went from a few hundred instances a year to thousands or tens of thousands. If there was a 0.5 percent chance that any given stablecoin transaction might be reversed, users might defect from them en masse, preferring instead the settlement assurances of digital bearer assets like Bitcoin. Barring a total wipeout of the stablecoin sector, I don’t see the dollarization of blockchains being reversed any time soon.

Waller’s second premise also seems secure. The dollar has been strengthening relative to most fiat currencies, as the US economy is generally stronger than the rest of the developed world. With China in crisis and the EU shrinking its economic role in the world, real competitors to the dollar seem as remote as ever. Empirically, no one seems to want Euro stablecoins. I do expect that as crypto becomes more entrenched and regulators pass protectionist legislation (such as the EU has done with their MiCA), we could see limited instances of non-USD stablecoins flourishing. But crypto is a global market, and the overwhelming dominance of dollar stablecoins evidences that when the sovereign walls come down, the distribution of outcomes settles in a kind of extreme pareto distribution. And after a decade of stablecoins existing and a $160b float, I think we have enough data to assert that the dollar dominance as UoA isn’t just a weird data artifact, but an actual indication of which currency the world prefers, if given the choice.

In my view, crypto markets are a natural experiment demonstrating that if state-level monetary barriers didn’t exist, there would be many fewer currencies than there currently are. It’s possible that nation states might try and reassert their waning monetary privilege by banning stablecoins or their liquidity nexuses like exchanges, as we are seeing in Nigeria, but this doesn’t seem to be very effective. Crypto-financial infrastructure is simply too ubiquitous, and grey and black markets create p2p crypto liquidity virtually everywhere, even when bans exist. So while I think the dollar’s share of stablecoin UoA may come down to the 90–95% range in the coming years as we see more crypto-protectionism at the state level, I believe that dollars will continue to predominate.

The most questionable part of Waller’s argument is actually the notion that stables are good for the dollar. They’re good for the dollar in the abstract sense that they distribute dollars (and dollar assets like US Treasuries) in a frictionless manner to virtually anyone on the planet with a smartphone. This will likely collapse weaker fiats with episodes of crypto-dollarization. However, they may not be good for the Dollar Establishment, as in the set of entities that benefit from the current configuration of the dollar system. As Massad says, stablecoins (if issued abroad, via less cooperative issuers) may impair the dollar sanctions regime that characterizes the dollar system today. If stables are able to retain their current permissioned pseudonymity privacy model (whereby most on-network transactions are p2p and largely unsurveilled), they may be bad for those in government who seek to express power by creating political conditions on whom can transact. And if stablecoins become truly successful and create a high-tech form of “narrow banks”, stablecoins could be bad for the domestic banking system — by accelerating the disintermediation of commercial banking. So stablecoins could well get the dollar into the hands of many more individuals worldwide, and even turn the dollar into an apex predator which collapses many weaker fiats, but it may not be good for the Washington Consensus — the dollar establishment in DC today. I’ll cover some more of the winners and losers in stablecoin-world in the final section.

5. Brooksism: Stablecoins can help keep the dollar the world reserve

Brian Brooks should be a familiar name to virtually anyone who follows crypto policy. Formerly Coinbase CLO, he was Trump’s Comptroller of the Currency, where he passed a rule banning banks from engaging in Choke Point style behavior and devised a federal charter for crypto and fintech firms. He’s probably the most pro-crypto admin official this country has ever seen.

Brooks penned an op-ed in the WSJ last year entitled Stablecoins Can Keep the Dollar the World’s Reserve Currency. Brooks’ argument is simple, and one I align with (and have echoed in my talks). The dollar is the world reserve, although its status is under threat. Trade is increasingly being invoiced in other currencies (especially after sanctions on Russia and the emergence of the Russia-Iran-China axis), and major holders of dollar assets, like China and Japan, are divesting.

Stablecoins by contrast represent approximately $160 billion of net new dollar exposure — and a substantial fraction of them are held by foreigners. Each of those dollar liabilities is backed, generally speaking, by dollar assets like short term treasuries or overnight repos. Ceteris paribus, more buy pressure for the debt makes it cheaper to service, and less makes it more expensive. The US happens to be engaged in historically elevated deficit spending and has a relatively high debt to GDP ratio, so we need all the buyers of the debt we can afford. Stablecoins are approximately 99 percent dollarized — and this tendency has held for their approximate 10 years of existence. Thus, their existence as the native collateral of crypto, and, long term, a dominant form factor for global digital money, is positive for dollar proliferation and creates a potentially large buyer of the federal debt. And crypto is increasingly synonymous with stablecoins. Historically, assets like Bitcoin or Ethereum served as crypto collateral types (SoV), media of exchange, and even units of account. This is no longer the case. Stables now dominate for margin and collateral at exchanges, quote currencies on these exchanges, and represent 70–80% of all value settled on chain (as I showed in my Token2049 talk last year). Stablecoins have won the MoE race in crypto, even if the most idealistic crypto-natives haven’t realized it yet. Blockchains are all about dollars.

This turns a common crypto-native talking point on its head. Far from eroding the dollar’s use globally, crypto — via stablecoins — seems to be extending it in a new digital terrain. We see incidents of crypto-dollarization taking place, notably in Venezuela, Argentina, Turkey, and Nigeria. (Castle Island is currently undertaking an on-the-ground survey to get a more quantitative sense of what is happening in certain highly-adopted EM markets). Stablecoins, being instruments that can be held directly in a fully sovereign manner with no intermediary, seem to be more credible to individuals in these countries seeking dollar exposure than, for instance, dollarized bank liabilities in their local banks. They are also highly liquid and available on centralized exchanges, via moneychangers, or local OTC networks. For many folks in the global south, stablecoins offer a dollar liability that is far more credible than dollar deposits in banks, far easier to access than physical USD cash, and one that can easily be deployed to earn interest in DeFi or the US T-bill rate (via an emerging cohort of natively interest-bearing stablecoins). Stables are globally liquid and can serve as remittance rails or settlement medium for cross-border commerce without the hassle of banks and other costly intermediaries.

Brooks’ views contrast with Waller in that Waller’s comments reflect a more passive view that even if crypto succeeds, it’s unlikely to threaten the dollar (and the dollar isn’t really under threat, anyway). Brooks by contrast takes the more active position that stablecoins should be encouraged because they could actually help rescue the beleaguered dollar.

Brooksism is the position I align with the most, but there are a few pieces that trouble me.

The first is the embedded assumption that the dollar as the global reserve is a desirable state of affairs. Following Pinketty and Lyn Alden, I’m not actually convinced that the dollar as the global reserve is actually good for most Americans. In fact, I’m persuaded that the dollar reserve is great for coastal elites who work in finance, for folks the government (and recipients of that patronage), and bad for the working class. The structural nature of the system is such that the US as the issuer of the global reserve must maintain a persistent trade deficit in order to supply the world with dollars, causing debt accumulation in the US, and an offshoring of manufacturing. (This concept is too complex for a full treatment here, but you can read Lyn Alden, the BIS, or Greely in the FT for more.) This setup causes the world to accumulate dollars (and dollar assets like US Treasuries, US equities, bonds, real estate, stocks), benefiting those who work in finance or those sectors. Meanwhile, the relatively strong dollar makes US exports uncompetitive relative to our supplier nations, causing our industrial sector to fade into irrelevance, immiserating a large portion of the population.

So, even though I have at times promoted the idea that continued dollar dominance is generally supportive of US interests, the truth is that we need to be specific with whose interests we are specifically interested in. Certainly, dollar dominance is good for US policymakers (they can spend more loosely), for DC-adjacents, for the US’ continued sanctions-making ability, and for individuals (like myself) who work in the US financial sector — globalized Capital, essentially. But it’s not, as far as I can tell, particularly good for the working class, or inequality generally.

One reason I would hypothesize this system persists even if it creates discontent and populism is simply that it’s extremely convenient for the US government to retain oversight over the global nexus of all financial transactions, especially as it gives policymakers the ability to project power (via sanctions) without exerting kinetic force. But this may be less of an incentive, especially as our sanctions-making power has meaningfully diminished in recent years.

So it could be said that if there is a rethinking of the petrodollar system, more commodities are invoiced in other currencies, the world de-globalizes, mercantilism re-emerges, the American industrial base is rebuilt, we become a competitive exporter once again, and we rethink our debt-financed, consumerist economy dependent on China, the prospects for the American middle class might actually improve meaningfully. For sure, stablecoins probably won’t move the needle much here either way. But I am always mindful of this possibility when I think about the “stablecoins promote the dominance of the dollar (and that’s good)” talking point. It may well be the case that the dollar’s dominance isn’t really good for most Americans — and the negatives are no longer offset by the perceived benefits like our sanctions-making ability, which is an increasingly blunt tool.

The second misgiving I have is simply a matter of scale. Although I have made the exact same case as Brooks in some of my talks (see my talk at Messari Mainnet in 2023), the fact is that stablecoins are still relatively minor in the grand scheme. At $160b in float, they are still a minor (yet growing) buyer of the debt. If they were a sovereign in their own right, they would be the 16th largest sovereign holder of Treasuries. If they were a money market mutual fund, they would be the 14th largest. But they don’t — right now — move the needle in terms of making the deficit cheaper to monetize. Stablecoins at ~$160b only represent 88 bps of US M1, and their holdings only 47 bps of total US government debt (at $34T). Large foreign holders of Treasuries like Japan ($1.1T) and China ($0.85T) are still multiples larger than the debt instruments held by all stablecoins. And it’s possible that a new cohort of stables that aren’t based on US treasuries and dollar assets emerges. For instance, Ethena (which is the fifth largest USD token today — they prefer “synthetic dollar” to “stablecoin”) derives its value from Ethereum and Bitcoin collateral, offset by short positions. Its success may do little for US interests.

All of this could change, of course, as crypto balance sheets continue to expand and the stable float grows as they become a major payments system. But for now, the “stables make the National Debt cheaper to monetize” concept remains a relatively speculative talking point.

The ought of stablecoins

It’s important to decouple the normative from the descriptive, i.e., what should happen from what is likely to happen. Where some of these thinkers go wrong, like Gorton and Zhang, is that they focus on ought rather than is. Because stablecoins shouldn’t work (according to G&Z), or because it would be bad if they worked (following Grey), they are dismissed. But the plain truth is that they are working, and in my view have achieved exit velocity.

It’s very clear to me that stablecoins aren’t going anywhere. They are by far the most important application of public blockchains. What started as a hacky solution to Bitfinex’ banking problems became the most important development in financial technology in decades, and our best chance at creating a true form of digital cash and regaining the ground we’ve lost on financial privacy in the last half century.

By my estimate, stables settle approximately 10 trillion dollars a year, a similar level to Visa (you can quibble whether this is an apples to apples comparison). Almost 100 million addresses on-chain hold stablecoins today. They are increasingly being integrated into major payments networks, such as those run by Visa, Stripe, Checkout, Paypal, Worldpay, Nuvei, or Moneygram, to name a few. The mythical convergence between crypto and tradfi is finally, actually happening, with stablecoins as the beachhead.

And even as the US continues to be hostile to stablecoins on virtually all fronts, new jurisdictions are embracing them. In most cases regulators acknowledge that the vast majority of stables are dollar-backed and are permitting dollar stablecoin issuance by local issuers. This growing list includes Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai, Japan, Bermuda, and others. Certain places, like the EU, take a more cautious view, passing stablecoin regs, while aiming to limit the influx of dollars through that vector. For stablecoin issuers though, all that matters is that there are a few safe havens that are willing to give issuers a reasonable regulatory terrain to operate on. And this seems to be the case.

Objectively speaking, therefore, it seems that stablecoins are here to stay, and will likely continue to grow untrammeled unless policymakers globally launch a coordinated campaign to destroy them.

On the normative front, my synthesis of the views summarized above is simply that each individual policymakers’ views are informed by their own political objectives and underlying views. Gorton and Zhang prefer a state monopoly on money. Many of the critics listed here tend to favor the exploitation of financial infrastructure for political ends to varying degrees. Thus, any cash-like network, especially one that’s particularly unaccountable, is hostile to this agenda. Massad (who appears to be a more moderate, Obama-style Dem) is more nuanced. He acknowledges the importance and historical significance of stablecoins, but is concerned about sanctions evasion. Brooks is a libertarian-leaning Republican, and is therefore strongly favorable towards stablecoins. Waller is a Republican-appointed Fed governor, and is able to see the conditional benefit of stablecoins for the dollar.

Normatively, I have libertarian sympathies, and strongly believe in individual liberty, a reversal of financial surveillance trends that began 50 years ago with the digitization of finance, and the right to financial self-determination. I am also skeptical of the US’ continued ability to deputize financial rails for political ends; this status quo appears to be ending (and I don’t particularly lament its departure). I am generally supportive of dollarization as a policy that promotes restraint in untrustworthy jurisdictions and therefore see the welfare benefits of spontaneous bottom-up crypto dollarization that we see happening today.

Stablecoins disintermediate banks, remitters, and in conjunction with other forms of crypto-financial infrastructure like exchanges, give billions of savers globally direct access to digital dollars that they may not have had before. In each case, disintermediation means cheaper transactions. We see this on the ground directly with remittances. Settling remittances on stables via exchanges shaves meaningful basis points off global remittance rates, which still average 6.2 percent according to the World Bank, although this varies by channel. For billions of individuals in the global south, this makes a meaningful difference.

Thus, for me, stablecoins — especially those that are truly cash-like (i.e., exhibit minimal embedded surveillance) — are an immensely powerful tool, and represent a largely unmitigated force for good globally, especially in countries with immature or unstable financial sectors. The downsides of stablecoins, such as more scalable illicit flows, can be managed as issuers become more aggressive with ‘freeze and seize’ policies, and law enforcement builds sophistication around blockchain analysis.

So who are stablecoins good for?

As with any disruptive technology, there are winners and losers in any transformation. Instead of labeling stablecoins “good” or “bad” broadly, I will segment by stakeholder my views of who they are good or bad for.

Stablecoins create opportunities for:

Individuals living in unstable currency regimes: the existence of this market is well-established. If you look at the IMF or Chainalysis data, it’s evident that crypto adoption correlates meaningfully with inflation, unstable monetary regimes, and past histories of sovereign default. Stablecoins offer a self-custodied, credible USD liability outside the banking system, and this is clearly attractive to individuals in places like Argentina, Nigeria, and Turkey where currencies and banking systems are not reliable.

Sophisticated ex-US financial hubs: just like the UK thrived as a hub due to the emergence of Eurodollars, certain jurisdictions have begun to see stablecoins (and crypto more generally) as an opportunity, especially when contrasted with the US’ reluctance to productively regulate the sector. Already, we see a flight of founders and capital from the US to these emerging hubs. The default place to launch a stablecoin today is outside the US.

Digital nomads: stablecoins renders savings far more portable on a cross-border basis. They also simply payroll, especially for businesses with globally distributed employees. Already, it’s common to see crypto-native employees asking for payment in USD stablecoins, both due to lower transaction costs and because their local currencies may be unreliable.

The US government (from a fiscal perspective): as mentioned, stablecoins largely back themselves with short term US government debt. Collectively they rank 16th among sovereign holders of the debt, and 14th among US money market mutual funds. While the scale of this activity is relatively small today, it’s not inconceivable that stablecoins collectively could become a top three holder of T Bills. This would meaningfully improve the US’ fiscal prospects.

Stablecoins create challenges for:

Foreign governments with unstable currencies: stablecoins make spontaneous dollarization (the likes of which we saw historically in Ecuador in 2000) much more efficient. I expect to see multiple episodes of crypto-dollarization over the next decade, whereby savers engage in currency substitution in a bottom-up manner, accelerating the devaluation of weak local currencies. Already, we see crypto exchanges and stablecoins blamed for a wave of dollarization and Naira inflation in Nigeria.

Banks: stablecoins accelerate the rise of narrow banking, or the transition from banks as the default savings devices for individuals and firms. They are part of the broader trend of a rotation towards fintechs, money market funds, direct Treasury ownership, and crypto instruments. If interest rates stay high (and as stablecoins increasingly pass along interest), a low-yielding savings account looks less attractive relative to a money market fund or an interest-bearing stablecoin.

Legacy financial gatekeepers: any financial business that benefits from regulatory barriers to entry (banks are the epitome of this) will likely face margin compression due to the increasing popularity of stablecoins. For instance, legacy remitters relying on the correspondent bank system will see their business model challenged, as they are forced to compete with digitally native remitters who can offer transfers more cheaply with crypto-financial infrastructure.

Law enforcement: stablecoins create a paradox for law enforcement. They are highly legible, and indeed records of illicit transactions are present on the blockchain forever, once on-chain addresses are linked to illicit entities. However, they also facilitate the (relatively) final settlement of value on a cross-border basis in a peer to peer manner at scale. Physical cash faces the constraint of being costly to move and store, and as such exhibits physical constraints on its use in illicit finance. There’s only so many banknotes you can stuff in a duffel bag and take on a commercial flight, for instance.

Stablecoins face no such scale constraints. But stablecoins are also subject to intervention by issuers who maintain “freeze and seize” capabilities. And these issuers do frequently interrupt illicit activity when they are made aware of it by law enforcement, at an increasing scale. (See for instance the seizure last year of $225m USDT linked to a crime syndicate.)

Unlike cash, illicit stablecoin flows can be frozen at a distance. It’s also, at present, easier for law enforcement or courts to reach out to a single stablecoin issuer rather than trying to wrangle a network of banks through which illicit funds are flowing. There’s only a handful of major stablecoin issuers (and they maintain active dialogues with law enforcement); there are thousands of banks.

It’s important to understand stablecoins as an evolving tool in the cat and mouse game between illicit actors and law enforcement. In the short term, illicit actors may feel that stables offer them more flexibility and convenience in terms of terrorist finance, scams, or money laundering, but as the sophistication of global law enforcement ramps up, I expect that they will be increasingly perceived as a relatively worse vector for illicit flows. However, as we are in the transitional period, there is rightly a lot of concern on the part of governments as to the possible use of stables for crime. Long term though, the fundamental higher legibility of stables plus the freeze-and-seize quality of these networks should make them overall less good for crime than cash — and possibly legacy digital rails too. This will of course require law enforcement to continue to grow their toolkit as it pertains to these networks.

The US national security apparatus: similarly, stablecoins will force a rethinking of the standard sanctions toolkit employed for foreign policy objectives. Personally, I’m very skeptical of the status quo in US sanctions policy. It appears to have manifestly failed in the case of Russia. As far as I can tell, the US seizing Russia’s reserves, and attempting to interrupt the flow of commodities to Russia via dollar networks has only accelerated de-dollarization. In 2023, 20 percent of oil trade volume was settled in currencies other than dollars according to JPM. This is mainly catalyzed by the emerging Russia-China-India-Iran commodity axis.

At the same time, sanctions don’t appear to have dissuaded Russia in its imperial ambitions or meaningfully impaired its ability to wage war. Nevertheless, Washington hasn’t changed course with its approach to sanctions, and you can see this thinking reflected in the comments made by Massad, who is chiefly concerned with stables interfering with US sanctions-making ability.

In my view, Massad is shutting the barn doors long after the horse has bolted. Nonetheless, if US policymakers want to deputize stablecoins for their decaying sanctions regime, they still can. They would have to encourage onshore issuance via sensible stablecoin legislation and encourage accountable, regulated financial institutions to become issuers (rather than keeping banks firewalled from the sector and making stablecoins toxic via edicts like SAB121). Their current posture, which pushes stablecoin issuers abroad, will only make enforcing national security directives via stablecoins more challenging. Already, it’s an open question as to how the US would exert pressure on Tether, the world’s dominant stablecoin.

The Treasury seems to be increasingly taking the perspective that any dollar liability, no matter the domicile of its issuer, end users, or backing assets, falls under the aegis of the United States. But this would call into the question the nature of the entire offshore market, and in my view, constitute a significant change in policy, and would likely accelerate the dedollarization which is already underway.

Reading list

- Rohan Grey in The Nation, Facebook Wants Its Own Currency. That Should Scare Us All.

- Gorton and Zhang, Taming Wildcat Stablecoins

- Timothy Massad in Brookings, Stablecoins and national security: Learning the lessons of Eurodollars

- Chris Waller, The Dollar’s International Role (speech), Reflections on Stablecoins and Payment Innovations (speech)

- Brian Brooks in the WSJ, Stablecoins Can Keep the Dollar the World’s Reserve Currency